Amanda and Gemma discuss fairy tale structures and symbolism in Yaa Gyasi's Homegoing, a moving debut about a divided family and slavery's cruel legacy:

Amanda Baldeneaux: I loved this book; I’d picked it up because I heard an interview with Yaa Gyasi talking about how she wrote the book using a family tree rather than an outline, which I thought sounded interesting. I don’t normally make it through books that aren’t plot driven, and I did take a break in the middle when life got busy because there wasn’t that plot push to make it through the too-tired-to-read nights, but I came back to it and still loved it. When I finished I had to just close the cover and try not to cry. I failed.

Gemma Webster: I first heard about Yaa Gyasi this past summer at the Lighthouse Writer’s Workshop Lit Fest. There was a panel of agents bemoaning the fact that they had passed on her and her beautiful book. I wrote down her name because their level of remorse spoke to me of overlooked genius and the extreme fallibility of the agent-query process. (There’s hope!) Homegoing is a creation tale at it’s best. I’m glad this genius writer and her work made it out in the world.

AB: This book should be required reading. I saw a graph that showed how many years it would take for African Americans to acquire the combined wealth that white Americans have, and this book drives that inequity home through story. You can’t finish this book and not ache for every family torn apart, every child separated from its parents. You can’t read it and not be changed; it’s especially important amidst the current conversations about racism in America.

GW: I wholeheartedly agree. There’s some debate on Fiction Unbound about whether or not historical fiction counts as speculative. I happen to think historical fiction is the definition of speculation, but with Homegoing, we get the fairy tale element and thus free reign. The first story plants us firmly in the realm of fairy tale. Baaba the evil mother/step mother gives Effia several interdictions, and we know Effia will have to break them to go on the quest/adventure.

AB: The first story opens like a classic fairy tale origin story, with the fire raging when Effia is born, setting up the “curse” that will haunt the family for generations.

“He knew then that the memory of the fire that burned, then fled, would haunt him, his children, and his children’s children as long as the line continued.”

Throughout the book Gyasi uses fire as metaphor for the legacy of slavery, a force that leaves “wreckage” behind without any concern for those hurt. Adding to the speculative element, the dreams Effia, Akua and other characters have speak to both them and the reader about the lasting impact of slavery.

GW: Adventure/quest is quite a euphemism for a story about slavery, but that is the structure that Gyasi chose. It’s a smart choice; using the fairy tale keeps Effia from feeling sorry for herself and prevents us from seeing her only as a victim of her circumstance. She is one, but we also know she is the hero/antihero. She doesn’t ask for our sympathy, but we give it willingly even as she ends up on the side of power in the slave trade.

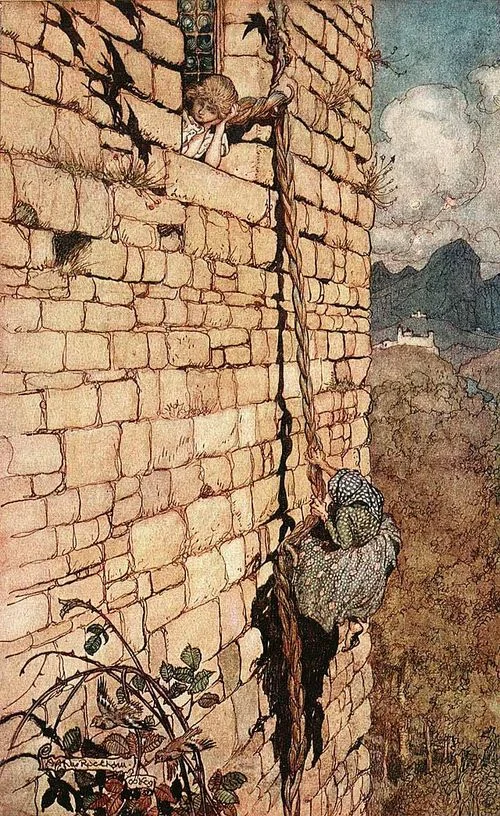

AB: Effia’s story reminds me of the princess-in-a-tower tales when she’s sent to live with her white husband in the Cape Coast Castle. The castle itself is rife with symbolism - the white castle set high over the village on the edge of the continent. It won’t immerse itself in the culture; it is something apart, trying to tear away pieces of Africa for profit, like Effia’s husband James Collins.

GW: I like the mixing of European fairy tale devices and African folklore (Anansi makes several appearances). The method serves the overriding metaphor of the entwined blood and history. The trajectories of the twin black stone necklaces that Maame gives to Effia and Esi are powerful symbols of both division and intertwining generations throughout the book. The nature of this jewel and the dividing of two (jewels and family lines) calls to mind the creation myth from their Zora Neale Hurston’s, Their Eyes Were Watching God:

“Here Nanny had taken the biggest thing God ever made, the horizon—for no matter how far a person can go the horizon is still way beyond you—and pinched it into such a little bit of a thing that she could tie it about her granddaughter’s neck tight enough to choke her. She hated the old woman who had twisted her so in the name of love. Most humans didn’t love one another nohow, and this mislove was so strong that even common blood couldn’t overcome it all the time. She had found a jewel down inside herself and she had wanted to walk where people could see her and gleam it around. But she had been set in the market-place to sell. Been set for still-bait. When God had made The Man, he made him out of stuff that sung all the time and glittered all over. Then after that some angels got jealous and chopped him into millions of pieces, but still he glittered and hummed. So they beat him down to nothing but sparks but each little spark had a shine and a song. So they covered each one over with mud. And the lonesomeness in the sparks made them hunt for one another, but the mud is deaf and dumb. Like all the other mud-balls, Janie had tried to show her shine.”

That same sense of loneliness and searching appears throughout Homegoing.

AB: The loneliness and isolation is a strong link to the hero’s journey's orphan motif. Effia was orphaned when she was sent to the castle, Esi lost both her parents when she was captured, Kojo was orphaned when Ness and Sam were recaptured, H was orphaned when Anna committed suicide, Marjorie was orphaned after her parents died of old age. So many broken families, all playing out Cobbe’s fear that the family was cursed. These continuous stories of parents and children are a strong metaphor for both Africa and her children/people, as well as slavery and its “children” (slavery’s enduring legacy, institutionalized racism, etc. - all of the things Marcus is studying at the end of the book that make him rightfully angry).

GW: The curses (fire, death, seeking, and loneliness) prove hard to shake. The curse motif is such a beautiful way to explore the horror of historical trauma. It also gives the characters something to fight against, giving them a sense of agency that inverts what we know to be true about slavery. The inversion allows the characters to retain their potential for power; they are strong people facing insurmountable odds. We root for them, we cry for them when they are crushed, and we root for the next generation because we know what has come before.

AB: The fairy tale-style curse is especially strong with Abena’s story.

“Abena’s father’s crops had never grown. Year after year, season after season, the earth spit up rotted plants or sometimes nothing at all. Who knew where this bad luck came from? Abena felt the seeds in her hand - small, round, and hard. Who would suspect that they could turn into a whole field?”

GW: This is both the original fire curse and doubling of the curse through payment to a magic being. This is the price Abena’s father paid to exit the slave trade. I love that Abena’s father comes to be called Unlucky. He has cast off his family, his name and his history, but he still can’t shake the curse. He bares the name willingly because he chose this fate. which was the lesser evil.

AB: We can’t talk about the fairy tale elements in the books without touching on Akua’s dreams. The firewoman holding two babies immediately made me think of Maame with Effia and Esi, but then as I read on, it made me think the firewoman is Africa, and the babies she mourns for are the people stolen by the slave trade. Then it dawned on me that both are probably true, as Effia and Esi are representatives of two trajectories of life for Africans after the slave trade began.

GW: Yes! There are children that perish and those who survive. The survivors, like Akua’s son, Yaw, carry the scars, the curses and the pain. But Gyasi doesn’t just leave it there because her characters are still powerful and human. They are forced to confront the things they carry and make a choice about how to live. I loved this moment between Esther and Yaw (Marjorie’s parents):

“My mother lives in Edweso. I haven’t seen her since the day I turned six.” He paused. “She did this to me.” He pointed to the scar, angled his body so that she could see it more clearly. Esther stopped walking and so Yaw stopped too. She looked at him, and for a second he worried that she would reach out and try to touch him, but she didn’t.

Instead she said, “You’re very angry.”

“Yes,” he said. It was something he rarely admitted to himself, let alone to anyone else. The longer he looked at himself in a mirror, the longer he lived alone, the longer the country he loved stayed under colonial rule, the angrier he became. And the nebulous, mysterious object of his anger was his mother, a woman whose face he could barely remember, but a face reflected in his own scar.

“Anger doesn’t suit you,” Esther said.”

AB: The end is really beautiful. Marcus, who said he “didn’t care for water,” and Marjorie swimming back to shore from the sea, like the lost souls returning home from the water that took them away and broke their families apart - so really, was it the water that was the curse, and not the fire? I also like that the author gave both characters in the present day “M” names, similar to the way she started the book with “E” names; it's an additional note that this is the reunification of the divided family, and the reunification of children of Africa with the mother, Africa. While I feel like the end is very happy, I’m still totally gutted by reading this book. Just thinking about the trauma and pain presented in the stories - and that they reflect true events - makes me… very sad. I can’t think of a better way to put it. But I’m so glad I read it and will push the book at anyone with the assertion that they need to READ it. Like, now. The stories have the power to foster the compassion that is lacking in so many conversations about racism and its presence in the US today.

GW: The more I think about the fire and water the more I realize that is sort of what I experienced reading this book; anger (fire) and sadness (water). I so agree with Amanda. Read this book. The beauty of the prose and strength of the characters will hold you while you fume, and cry, and still find joy in the reading.

Read Similar Stories

Carmen Maria Machado’s genre-bending memoir is a formally dazzling and emotionally acute testimony of an abusive queer relationship.