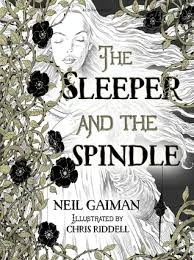

Neil Gaiman has tackled the subject of sleeping and dreams before, in his landmark comic series The Sandman. What he hasn’t done before, is concoct a fairy tale retelling that speaks directly to children as much as adults, with veiled Grimm-like warnings about the trouble with misbehaving. In this retelling, though, the ones misbehaving are the elders.

The Sleeper & the Spindle is a richly illustrated modern fairy tale that blends the stories of Sleeping Beauty and Snow White into an almost unrecognizable retelling. Like the original stories, the characters here are nameless, identified only by their titles of “Queen,” “Dwarf,” “Girl,” and “Old Woman.” When a group of dwarves travel beneath a mountain to a silk market, they learn that a sleeping sickness is slowly creeping across the land, freezing animals and humans in time and place. They return to the Queen, whom we recognize as a post-poison-apple Snow White, to warn her of the danger. The Queen is not living very happily ever after. Having set her armor, sword, and adventures aside to fulfill the duties of her title, she feels frozen in her own sense of boring stasis while awaiting her wedding day, when the prince will rise above her to the title of “King.” Unbound Writers Mark Springer and Amanda Baldeneaux discuss what makes this fairy tale re-imagining so unique in a saturated genre.

Mark Springer: Right away, Gaiman brings in the theme of dreams, the subconscious, and awakenings. Even in the book’s dedication, he and the illustrator, Chris Riddell, dedicate the story to their daughters, with Gaiman using the language, “For my daughters who woke me up.” The physical landscape of the story is bisected by a mountain range that not even crows, the symbol of second-sight and deeper understanding, are able to cross. On the Queen’s side, everyone is awake and going about their business. On the sleeping side, everyone is essentially a zombie, dreaming away their lives in a state of frozen youth. The dwarves and the Queen have to tunnel under the mountains, literally digging into the subterranean world of the subconscious and the imagination to enter the land of dreams.

Amanda Baldeneaux: But the dreams have been corrupted. The false sleep plaguing the land is an evil magic spell, and people are essentially decaying-alive, despite their preserved youth. The Queen can resist the spell, at least enough to carry on, because she has been under the same spell before, when her step-mother poisoned her. She knows the allure of sleep is false, and is determined to stay awake. As she goes deeper into the woods, the ghosts of her past are conjured around her.

Snow White, From the book of German fairy tales, Märchenbuch, c1919. WikiCommons

MS: We even see a reference to the original Grimm’s story of Snow White, where her evil step-mother is forced to dance to death in iron shoes.

AB: That makes it clear, in addition to the adventuring and sword wielding, that this ain’t no Disney Snow White. She has done something cruel out of vengeance. When the ghost of her mother tells her she is “So beautiful…like a crimson rose in the fallen snow,” the image we get is one of blood on innocence.

MS: It further drives home the point that you can’t get lost in illusions and the superficial appearances of things. One has to be grounded in reality, in the depths and complexity of life.

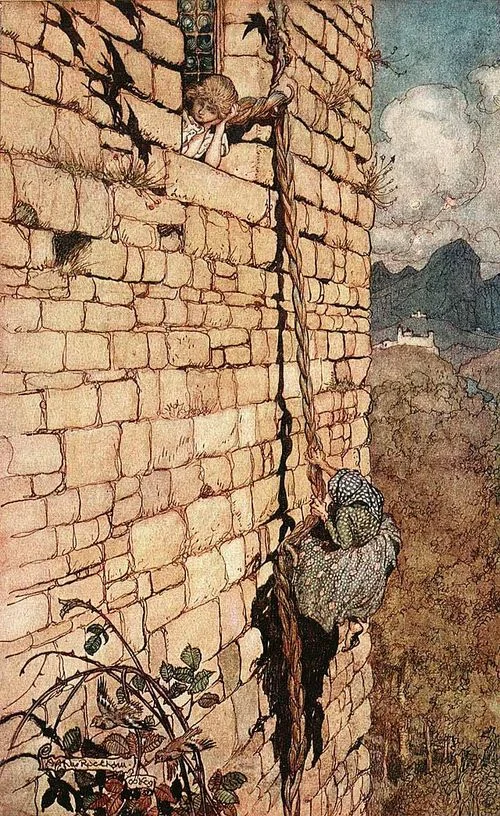

AB: The story itself shows us that even what we think we know can be more complete and nuanced than previously realized. This retelling is a big reversal of the girl-in-the-tower trope and the sleeping-dead-girl trope. It’s the Queen who goes out to save the kingdom with her sword at her side. It’s the prince who grins like a schoolgirl when she kisses him goodbye. And it’s the witch who is in the tower, sleeping, by her own design.

MS: To fulfill the desire to be young, beautiful, and adored. The entire story speaks to the idealization of youth and the inevitability of time. Even if you could freeze it, you can’t escape it. It’s a commentary on a youth obsessed culture, where children are idolized because of their surface-beauty, and the wisdom and experience of the elderly is considered second tier when weighed against physical beauty.

AB: Like the dwarves in the beginning, who thought that the ruby they had dug out of the mountains with their own hands wasn’t worth giving. They had to journey to find something else – precious silks – the perfect symbol for fashion, vanity, and something thin, short-lived.

MS: Gaiman wants us to realize that the best thing we have is what we already have: ourselves. Our experiences. Our imagination. The sleeping people are stuck in youth, but their lives have no meaning. They are draped in cobwebs and trapped behind a wall of thorns that is literally dead on the inside, with living flowers only growing on the exterior. On the inside, it’s a graveyard of bodies who have tried to penetrate it.

Henry Meynell Rheam's Sleeping Beauty, 1899. WikiCommons

AB: The sleeping girl is exactly that. She’s beautiful on the outside, having stolen the youth of the Old Woman, the actual princess, but she’s destroyed by a single scratch. Her insides are hollow. She’s slept for 70 years to regain the illusion of beauty, and wasted the most valuable thing she initially had: time. We trade our own time to work, but many of us aren’t doing it at a subsistence level. We give away extra time for little luxuries, for nicer houses and nicer clothes.

MS: And the sleeping girl, the witch, who is trapping everyone inside the dream of idealized youth, is the spider at the center of the web, pulling the strings. Her one desire is to be loved and adored, but the Queen says no.

AB: The Queen does a great refusal of the expectation that is so common, especially, I think, in girls: to react according to how others expect you to react, and to feel how they want you to feel. The Queen refuses to feel what the witch wants. Gaiman writes, “Learning how to be strong, to feel her own emotions and not another’s, had been hard; but once you learned the trick of it, you did not forget.”

MS: That’s the lesson of the tale, to find the strength to make your own choices, and to rise each new challenge as it comes.

AB: To write your own story. It’s not enough to just dream it, you have to be awake, to live it.

MS: And recognize that you are your own person, and not your title. The Queen rides off into the sunset with her dwarf companions, eschewing her role as Queen, a role that didn’t fit her.

AB: A female character who is a Queen, not a princess, and who chooses to ride off to more adventures. I like it.

Carmen Maria Machado’s genre-bending memoir is a formally dazzling and emotionally acute testimony of an abusive queer relationship.