At Fiction Unbound, we rarely miss an opportunity to stan for Carmen Maria Machado, author of the award-winning debut collection Her Body and Other Parties, essayist, and occasional witch. With In the Dream House, Machado applies her ranging intelligence, emotional acuity, and formal inventiveness to memoir: Dream House recounts Machado’s abusive relationship while a graduate student at the Iowa Writers Workshop, placing it within a larger context of domestic violence, particularly the underwritten history of lesbian and queer abuse. Fiction Unbounders Theodore McCombs and Gemma Webster take a deep dive into the text together, tracing how Machado shakes up the memoir and connects her irreverent genre play to the deep terror of her story. [Warning: spoilers for formal tricksiness follow.]

Theodore McCombs: Let’s talk about Dream House as Memoir. Obviously, we’ve got a weird one here, full of highly visible formal structures—and just to make up a working definition, we’ll call “formal” any device that draws the reader’s eye to the text’s architecture, how words are put together on the page. For example, the book is broken into short, sharp chapters whose titles are variations on the same phrase: “Dream House as Confession,” “Dream House as Epiphany,” “Dream House as Naming the Animals.” Machado drops footnotes to Stith Thompson’s classic folk tale taxonomy, Motif-Index of Folk-Literature, commenting on the action by connecting it to tropes from mythology and fairy tales. (The full title of Thompson’s motif-index is so wonderful, at first I didn’t believe it was real.) Machado intersperses her narrative with commentary on sci-fi and fantasy shows like Angel and Dr. Who, an analysis of a beloved Star Trek: TNG episode, and references to lesbian scholarship and queer theory.

So, what’s going on here? As “Dream House as Prologue” sets out, stories about domestic abuse within queer communities generally have been left out of the official record—the histories, the police reports, the sociological studies—until recently, and pop up only partially or obliquely. Conventional testimonial strategies have failed to adequately represent this experience, the implication being that we need unconventional strategies to do so. Looking at the strategies that Machado deploys, how do you think they hold up?

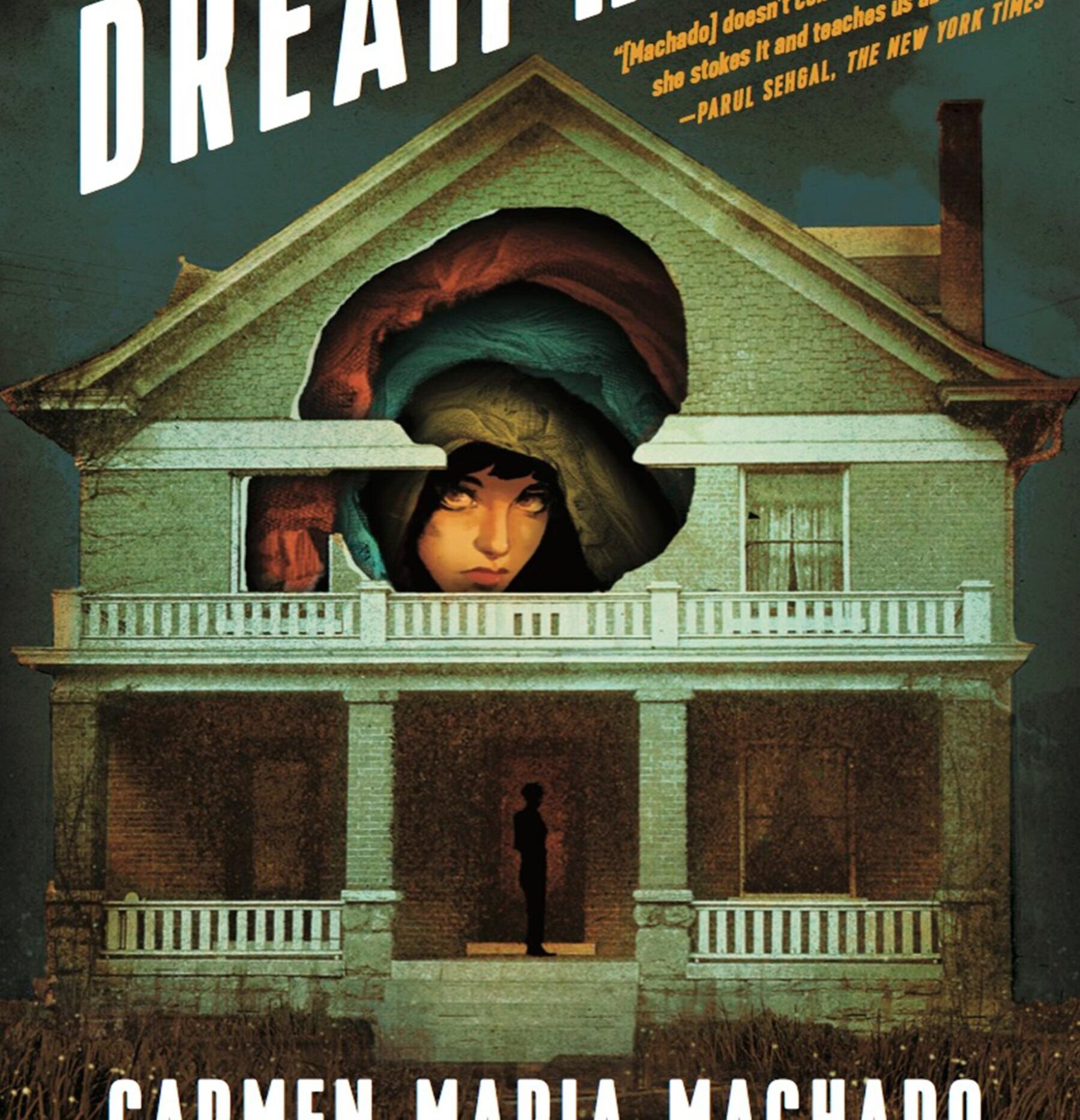

Gemma Webster: One of the things I look for in a book, especially memoir, is access to another person’s consciousness. So there’s something of a dodge, a secretiveness in the pastiche and pop culture analysis. This makes chapters like “Dream House as River Lethe” stand out, when the formal devices give way to an immediate, emotional experience of fear and great beauty. But there’s a way in which that secretiveness follows the Gothic genre: a haunted house slowly gives up its secrets, which build in intensity as the narrative goes on. The book’s own cover art previews this: the layers of the house being stripped back to reveal the consciousness inside it.

Cover art for In the Dream House (Graywolf Press 2019)

TM: Right, Machado invokes that genre explicitly in “Dream House as American Gothic,” where she discusses the Gothic romance. In stories like Rebecca or Gaslight, the house, full of danger, and the charming stranger who is not what he seems, lend forms to an experience that 20th-century women were just starting to publicly articulate as abuse. Gaslight literally names a specific form of emotional abuse (“gaslighting”), and by doing so, gives us power to counter it. By walking us through the paces of how the heroine is brainwashed by her abuser—and by the environment that gives him the power to do it—the story gives people who have experienced similar abuse a sort of map or rubric to understand their own experience, reorient, and hopefully, escape the trap. (In her chapter on fairy-tale silence, Machado cites Thompson’s Motif-Index, Type C432.1: “Guessing name of supernatural creature gives power over him.”)

GW: So the postmodern devices that Machado uses around her direct experiences actually give us a kind of access to her consciousness, after all: it’s her experience of abuse, but also what made that abuse possible—both individually and societally—it’s the confusion of influences, the way the individual and the environment are permeable. There’s a recurrent mention of the fact that the front door of the Dream House is never used, never open. In “Dream House as World Building,” Machado tells us in her dreams this door green, but it never was, not in waking life. Machado’s telling is so specific that this closed door holds up to its metaphoric weight without succumbing to cliché. It summons the archetypical requirement of hiding, of silence.

TM: And yet those influences that permeate her experience still don’t quite fit her. As she points out, Gothic romance is a heteronormative genre. If it’s a map, it maps imperfectly on to the situation queer women face. That ambivalence runs throughout the book: how important the references available to her are in understanding her abuse, yet how they fall short, in a way that makes her more vulnerable and alone in her experience. That’s the case with those chapter titles: their variations on “Dream House as ____” are like a searching, obsessive attempt to fit her experience into an existing form. And that’s especially the case with those amazing motif-index footnotes.

GW: Let’s talk about those footnotes! The index of tropes Machado references is a guide to the recurrence of themes in myths and folktales, single-phrase summonings that crisply set out the common narrative elements. Machado deploys these footnotes in a way that loosely calls to mind that postmodern playing around with paratext popularized by David Foster Wallace, but she’s doing something very different. The footnotes chime in to pin down the behaviors that Machado is partaking in that link back to archetypal narratives. (For example, after describing an exchange with her homophobic aunt, during which her mother fails to defend her, Machado drops footnotes citing “Type S72, Cruel aunt.” and “Type S12.2.2, Mother throws children into fire.”)

I was interested in how these footnotes bring in a seeming expert, external judgment on Machado’s world; it gives the sense Machado is not judging the people around her (or herself) to be monsters, ghosts, taboo-breakers, or cruel aunts, as much as that judgment is rational, objective, scholarly in a classical way, and, notably, male. It’s an interesting way to play with authority and to make us readers ask ourselves how we come to believe in the truth of a story.

TM: And doesn’t that get at one of the paradoxes of queer abuse that Machado’s teasing out? I mean, if we say, “queer abuse suffers from namelessness,” from a lack of those forms that help people recognize abuse and the guidelines to help them extract themselves, then we also have to recognize that queerness is all about rejecting old names, old forms, and old guidelines. The queer project is to break new ground in sexual relationship—or it’s supposed to be—sometimes, at least—to dismantle old ways of thinking and build something new and freer.

GW: Yes, she talks about this in “Dream House as Fantasy,” that loss of lesbian utopian thinking that abuse provokes. And here, her footnotes actually move away from the masculine gloss of Thompson’s motif-index—the hegemony she’s been borrowing and fitting her story into—and into direct quotes from lesbian and queer scholars.

TM: It’s a perfectly suited effect, and a reflection of how thoughtful she’s being about her formal play. For me, the most exciting part was realizing Machado has all along been using her virtuoso writing style, with all those conspicuous, even baroque formal constraints, to set up an exploration of abuse as a formal constraint itself. In “Traumhaus as Lipogram,” Machado compares the stilted, self-constrained texture of a lipogram—essentially a word game, in which one writes a text with a common letter of the alphabet avoided—to the disabling constraints a person experiencing abuse accepts or even self-imposes within the abuse:

A woman hid my thing and I can’t find it again. That’s just how it is. I cannot find what’s missing. I am trying and trying, and I cannot; as I fail, I shrink. I shrink down into dirt, wood worms. … Folks say nothing but Why didn’t you go / Why didn’t you run / Why didn’t you say?

(Also: Why did you stay?)

A little later, in another one of Machado’s bravura narrative moves, she constructs a Choose Your Own Adventure sequence that, when read according to the instructions, traps the reader in an unforgiving cycle of recrimination, apologies, and cruelty, and, when read in sequence, out of the set order, berates you for your disobedience: “Here, you are; a page where you shouldn’t be. It is impossible to find your way here naturally; you can only do so by cheating. Does that make you feel good, that you cheated to get here?” You can’t win: that’s the point of abuse.

It’s standard MFA doctrine to say form is content—that the syntax and structure of a sentence informs its meaning, or vice versa—but Machado takes that to such an ambitious and fearless place, it’s unlike anything I’ve seen. Her formal devices link the author-reader power dynamic to the abuser-abused dynamic, with the reader’s unthinking receptivity to the text, their perfect vulnerability to the page, standing in for a lover’s trust in their abuser. It’s a great idea on paper, and the fact that Machado pulls it off with such beauty and emotion is—I mean, what can I say, it’s an unqualified miracle.

Gustave Doré’s illustration for “La Barbe Bleue” in Contes de Perrault (1862)

GW: In “Dream House as Bluebeard,” Machado reinvents the folktale of the man who keeps his murdered wives in a secret chamber and entrusts his new wife with all the keys to the house but that one, fatal room. Of course she goes in: the breaking of the taboo is vital to fairy tales, otherwise the status quo is maintained, there’s no story. Machado’s idea is that if the wife hadn’t broken the tattoo, Bluebeard would have only escalated with more and more outrageous demands on her silence and obedience. That’s another important fairy tale taboo: the imprecation not to speak, and Machado constantly returns to it. At one point, her girlfriend even literally tells her, “You can’t write about this.” But just as Bluebeard’s wife breaks the imprecation not to open the door, Machado breaks that silence—and it’s one that needs to be broken.

In the Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, in her introduction to Perrault’s “Bluebeard,” Maria Tatar reminds us fairy tales were originally intended for adults and were “told around the fireside and in the kitchen. ... Gossip and gospel truth, gossip as gospel truth, these stories, often referred to now as old wives’ tales, represent a buried narrative tradition, one that flowed largely through oral tributaries as women’s speech,” until male editors and collectors channeled it into print. It’s fitting, then, that Machado reclaims “Bluebeard” and other fairy tales as her own story, returning them to the higher purpose of story; which is not merely to entertain, but to enlighten, to teach, to press us all deeper into our humanity, to be better to each other, and to recognize danger before it’s too late.

* * *

In the Dream House is out November 5th from Graywolf Press.

Cadwell Turnbull's new novel — the first in a trilogy — imagines the hard, uncertain work of a fantastical justice.