In parts one and two of our Southern Gothic series, Unbound Writers Lisa Mahoney and Amanda Baldeneaux examined Southern Gothic short stories and novels including genre-defining classics. Today, we spoke with the author of new southern gothic novel The Past is Never, Tiffany Quay Tyson. The book, set in the deep south of Mississippi and the Florida Everglades, is a coming-of-age story with a mystery that threatens to permanently shatter an already divided family. Tyson is a Mississippi native and Denver transplant, teaching at the Lighthouse Writers Workshops (including a craft class titled "Going Gothic" on June 14th during the second week of Lit Fest).

Amanda & Lisa: In our Southern Gothic series, we discussed what classifies a book as “Southern Gothic.” We saw many elements in your novel that ticked the boxes on our checklist, including ghosts and curses, a lack of autonomy, superstitious beliefs, and so much more. What do you think qualifies a book as Southern Gothic, and did you have it specifically in mind when writing The Past is Never?

Tiffany Quay Tyson: I did come to this story with the Southern Gothic in mind. I love to read books with a bit of Gothicism (southern or otherwise), and I try to write books I’d want to read. When I think of Southern Gothic, I think first of Flannery O’Connor. I love the way she tangles up religion and superstition with violence and brief moments of redemption. It’s beautiful even when it’s awful. I am always interested in the ways that religion is used to justify violence, exclusion, oppression, and fear in the south and elsewhere. My characters are often more superstitious than religious, but ultimately religion and superstition are the same thing. Ghosts and spirits, curses and plagues, fate and divine intervention; it’s all part of the same package. People want to believe in something. They want a set of rules to make sense of the world. That’s not a bad thing, but sometimes it leads to terrible actions. That’s what I like to explore when I’m writing and gothic elements work really well in that exploration.

As for what makes a book Southern Gothic: I think any book set in the south that incorporates mysticism, death, and decay probably qualifies. Another thing that is pervasive in Southern Gothic fiction is a sense of creepy nostalgia. The characters in these stories are often desperate to hang on to a particular way of life, even as the trappings of that life crumble around them. They don’t bury the dead, they cling to them. That’s bound to result in a few hauntings.

A & L: Escaping the past (or attempting to) is a theme throughout the book. How do you think the south as a whole is faring in its efforts to escape its own past?

TQT: I think the south takes one step forward and two steps back when it comes to escaping its past. The issue is that plenty of southerners have no desire to. They're nostalgic for it. There are progressive southerners, of course. There are people speaking out forcefully for a better future for the region, but it’s a tough sell and one that many people never hear.

There are sharp class distinctions in the south. I think in most places in America you’ll find that highly educated, affluent families don’t mingle much with working class or poor families. But in the south, a working-class family that owns its own home and a working-class family that rents a trailer on a plot of land are distinctly different. And urban poor is not the same thing as rural poor. These small distinctions keep people apart, even though they might benefit from working together. There are exceptions, of course, but plenty of people in power believe that pitting southerners against one another is a good strategy. If poor people are busy fighting each other, they won’t have time to notice that they are being kept poor by the people encouraging them to fight. And if middle-class southerners can be convinced that helping other people will mean they have less, then they will keep looking over their shoulders to make sure no one is rising up instead of looking forward to see the politicians picking their pockets.

A & L: What role is literature playing in these efforts?

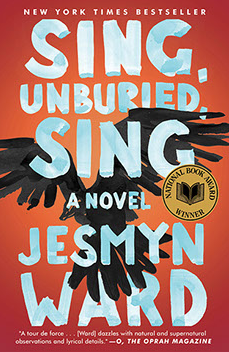

There is hope in literature. Southern writers tend be progressive, and I firmly believe that literature can change minds and change perspectives, but it takes time. The south has always churned out great literature, and the region’s writers have always tackled race and class and the ongoing legacy of slavery. Still, the south is where it is in spite of Faulkner, in spite of Eudora Welty, in spite of Richard Wright. Now we have writers like Jesmyn Ward (Salvage the Bones and Sing, Unburied, Sing), who is arguably one of the best American writers working today. Angie Thomas's young adult novel The Hate U Give, about a girl who witnesses the police shooting of an unarmed black man, has spent the past year on the New York Times bestseller list. Both of these writers are black women from Mississippi. These women are the future of the south if the south has any sense at all, but there are definitely people fighting against that future.

A & L: The novel is largely about families and what comprises a family, with traditional molds continuously broken and re-examined throughout the story. Do you think stories of happy families and love can coexist with the elements of southern Gothicism?

TQT: I don’t know about happy families. Every family has problems and secrets. I don’t think happy families would be all that interesting to read about or to write. That said, happiness can definitely exist within a gothic tale. People find moments of happiness amid real-life atrocities, so there’s no reason a fictional character can’t find happiness in a gloomy situation. Also, I think it’s true that many people are happiest when things are dark. It gives them a sense of purpose.

Love can definitely flourish in a gothic tale. Gothicism is romantic and it’s the perfect setting for all sorts of love stories. In my book, I focus mostly on familial love. I do believe that we construct our own families and that blood is only a small part of what binds people together. Of course, gothic elements are also excellent for romantic love stories. The lovers may be doomed, but that doesn’t make their love any less real.

A & L: Bert, the middle child in the Willett family, is speaking through the lens of memory, and therefore by default an unreliable narrator. What is the difference between writing reliable and unreliable narrators, and what leeway does an unreliable narrator give you when telling a story steeped in myth?

TQT: I prefer unreliable narrators whether I’m reading or writing. I’m interested in the way stories change and evolve depending on who is doing the telling. You get a group of people together and ask them to tell you about an event they witnessed and every one of them will tell you something different. Most of them will be telling the truth, but it’ll be a truth clouded by experience and prejudices and blind spots. Heck, it’ll be different depending on who they are telling the story to and when. You don’t tell the same version of a story to your best friend and to a young child. You edit based on your audience. I love that. I think we learn so much about people by the details they choose to include and the ones they omit. In this story, Bert is obsessed with finding the truth and what she discovers is that truth is complicated. So how does she tell the reader about her journey? What matters most to her? Those are the sorts of questions that make writing fun. As a writer I figure out who Bert is by what she notices. That’s far more exciting to me than a strict, factual retelling. What she learns, of course, is that the truth is more complicated than right and wrong or good and evil. And she discovers that the stories other people tell can be truthful, even when they aren’t completely factual. These myths and legends give Bert a way of making sense of the world.

A & L: Bert exercises modern freedoms that earlier generations of southern women like the character Granny Clementine helped win, yet her history is also trapping her in traditional female roles. Do you think this is an issue the south (or even the US as a whole) is making progress on or still struggling with?

TQT: I think the whole world still struggles with the expectations of traditional gender roles. In the south, a lot of this has to do with the strong influence of religion on day-to-day southern life. Men are the head of the family and of the church. Women are expected to serve as the man’s helpmate. It’s a terrible message for young girls. You look at someone like Paige Patterson, who was an icon in the Southern Baptist community for decades. Patterson was only recently stripped of his position as the head of a Southern Baptist Seminary after years of counseling abused women to stay with their husbands and discouraging rape victims from reporting crimes to police. Patterson thought (and probably still thinks) that he was right. He was telling women to support men and that’s what a lot of religious leaders believe a woman is put on this earth to do. Girls raised in strict religious communities or households have to shake off those teachings before they can speak out against a man, not only because he is abusive but also because he is wrong. A lot of women cannot get past their upbringing to do that. This not strictly a southern problem, however. Look at all the scandals in the entertainment industry. The Hollywood studio system and the Southern Baptist Convention are basically the same organization. Both operate under a system that silences women while protecting abusive, power-hungry men. That said, I do see evidence that things are changing. Women are speaking out more forcefully and demanding a place at the table. They are sitting at the head of many tables. We still have a long way to go, but I am optimistic about the female future.

A & L: The novel is steeped in lore and legend. What stories or myths most inspired this book’s writing?

TQT: Some of the stories I drew on came from family tales that I distorted and reimagined, some were pure imagination, and some were inspired by legends or by history. The south is a very rich place for stories. My father grew up in Natchez, Mississippi, where there’s this deep depression on the river bluffs that they call the Devil’s Punchbowl. It’s supposed to be haunted and there are all sorts of stories about its past, the worst of which is that it served as a concentration camp for freed slaves in the era of emancipation. The able men were captured and forced to work with Union forces, but the women and children were dumped in this pit and starved to death. More than 20,000 people were reported to have died there in the course of one year. Now the area is rich with peach trees, but a lot of people won’t eat from those trees because they know what fertilized that fruit. My place is fictional and the history is different, but I was interested in the idea that the history of a piece of land might make it evil.

I am also interested in stories of the paranormal, which I used a bit in creating the character of Bubba Speck. In college, I took a course called Science & Pseudoscience from a great professor who claimed to have firsthand experience with UFOs. This man was a serious scientist who believed in the possibility of life beyond Earth. The course also included discussions about things like auras and ESP and mind control. It was fascinating. I am skeptical by nature. I have a hard time believing in things I can’t see, but I’m a little like Fox Mulder on "The X-Files." I want to believe. So I’m often giving my characters some sort of supernatural belief or ability or encounter and then I work to debunk those myths on the page. It’s a way of arguing with myself about what I believe and what is possible.

A & L: The title is a snippet of a quote from Faulkner. How does the title build on or subvert the original quote? Did Faulkner influence other parts of the story?

TQT: I chose that title early on because I love that quote from Faulkner, but I kind of expected I would change it at some point. My hesitation in using such a direct Faulkner reference was that someone might imagine I was comparing myself to Faulkner, which was never my intention. I did work with a wonderful editor who wanted to consider other titles and I was happy to do that. We brainstormed and went back and forth on different ideas, but ultimately stuck with the Faulkner quote. Neither of us could come up with something we liked better. Proof, I suppose, that you can’t really improve on Faulkner’s words.

And the novel, once finished, really was about how the past puts its thumb on the future and how hard it is to escape the cycle of your own family and community. So in that way, I think it builds on the original quote. It also, however, explores how a person might begin to break away and tell the stories of the past with new perspective. In that way, I hope it’s a bit subversive. Bert won’t ever shake free of her family’s past, but I can certainly see her telling those old stories in new ways.

A & L: How has/does being a native Mississippian influence your writing? Has adopting Colorado as your home state changed or influenced your perspective on regional writing?

TQT: I don’t think I had any perspective on being a Mississippian until I moved away. When I graduated college, the country was in a recession and jobs were hard to come by. I managed to land a job as a newspaper reporter in the Mississippi Delta. I worked there for about a year, before leaving the state at the age 21. It was kind of a brash decision. I went to Austin, Texas, which is not the south despite its geographical location. I ended up working with the PBS station as the publicist for Austin City Limits. It felt like a miracle to land that job. It proved to me that I could survive outside the south. Years later, I took a job in Denver even though I had no connections or friends here. Again, it was kind of a brash decision, but it worked out. I had done some fiction writing in college and while I was living in Austin, but it wasn’t until I got to Colorado that I really got serious about my writing. I joined Lighthouse Writers Workshop and took a bunch of classes. I began to discover my voice and my writing style. What I learned was that I loved living in Colorado, but I couldn’t seem to stop writing about Mississippi. When I’m in the middle of a place, it’s hard for me to see it with any clarity. I need some distance to sharpen my perspective.

I don’t think living in Colorado has changed my views on regional writing except that it’s made me aware of how narrow our reading habits tend to be. There is nothing about southern fiction that makes it inaccessible to readers from Brooklyn or San Francisco or Portland. In fact, those readers would probably love southern fiction, but they don’t hear about most of it. Southern fiction is marketed to southerners and only a few writers ever break out of those regional designations. In general, I wish we had fewer pigeonholes for books or I wish more readers would choose books outside of their narrow comfort zones.

A & L: What do you most want readers to take away about the south after reading one of your novels?

TQT: I want readers to understand that southerners are people and not caricatures. Picturing the south as a place where everyone lives in ignorance and poverty is no more accurate than picturing a south where all the houses have wraparound porches and fainting couches. I hate those memes and posters that reduce the south to a place defined by sweet tea, fried chicken, and devotion to Jesus. There’s such a strong temptation to stereotype southerners and it drives me nuts. I hope my writing does something to dispel those sorts of stereotypes and tired tropes. The south is every bit as complicated and interesting and maddening as the rest of the world.

A & L: Who are some of your favorite writers – southern, Gothic, or other – that you think the world should be reading?

TQT: Well, I tend to be in love with whatever writer I’m currently reading. I’m preparing to lead a Reading as a Writer workshop on Sarah Waters’ first novel Tipping the Velvet and I would definitely recommend Waters' work to anyone. She does include Gothic elements in a few of her novels, particularly The Little Stranger and Affinity. Plus, her writing is beautiful.

But let me focus on southern writers or we’ll be here all day. I’ve already mentioned Jesmyn Ward and Angie Thomas. I would also recommend the novels of Michael Farris Smith and Kent Wascom, and the short stories of Ron Rash (also his novels, but his short stories are stunning). In the Southern Gothic realm, I definitely recommend William Gay. (Here is our review of his novel, Twilight.) His career was too short. He published his first novel in 1999 and passed away in 2012, but he left us with some great writing. Recently, I was impressed by Margaret Wilkerson Sexton’s debut, A Kind of Freedom. I liked Kelly J. Ford’s Cottonmouths, a female driven grit lit debut set in the Ozarks. I could go on and on, but I won’t. My primary recommendation is that everyone try to read one or two books a year that are completely different from the books they normally read. I think it makes us better readers when we expand our literary worlds. I know it makes us better people.

Need more Tiffany? Check out her first novel, Three Rivers, or sign up for one of her classes at Lighthouse!

Carmen Maria Machado’s genre-bending memoir is a formally dazzling and emotionally acute testimony of an abusive queer relationship.