It’s a strange time to be contemplating agency. I mean both the noun, in the sense of action or intervention to produce a particular effect, and William Gibson’s latest novel.

As I write this, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread in the United States and around the world. Confirmed cases are increasing at exponential rates. Every news update brings word of more deaths, and more disruption—school closures, remote-working directives, event cancellations, travel bans, an entire European country quarantined, panic-buying, the global economy not so much slowing as slamming into a brick wall. Things are changing so rapidly, its pointless to bother with details; even a broad-stroke summary will be hopelessly out of date by the time you read it.

A crisis demands action. We’re hardwired to respond to threats against our safety and the safety of others. But the scale of this crisis is paralyzing. Global contagion. The very real possibility that billions will be infected, and millions will die. No individual action, no matter how heroic, is going to turn this tide. There is no dragon to slay, no Death Star to destroy, no supernatural boon to wrest from the underworld for the community’s salvation.

Instead, the best thing each of us can do, unless we’re one of the relatively few people on the front lines of the pandemic response, is to implement the recommended social-distancing protocols and wait. It doesn’t feel like taking action—it feels like doing nothing. It feels like helplessness. It feels like having no agency at all.

Which brings me to William Gibson. Agency, his latest novel, is a paradox. Despite its title, the book’s main characters, Verity Jane and Wilf Netherton, spend most of their time observing the actions of others, while events unfold around them. This violates one of the cardinal rules of storytelling: THOU SHALT NOT HAVE PASSIVE CHARACTERS. And yet, Gibson makes it work. So well, in fact, that I read Agency in three breathless sittings, thrilled and completely satisfied. Thus, the paradox.

My original take was something along the lines of THIS BOOK SHOULDN’T WORK BUT IT DOES AND I HAVE NO IDEA WHY AND THAT’S OKAY WILLIAM GIBSON CAN DO WHATEVER HE WANTS SIGN ME UP FOR THE NEXT ONE THE END.

Then COVID-19 went global, and everything I thought I knew about what it means to have agency changed.

Here’s the part where you need to know a little bit more about the book. Agency is a sequel to Gibson’s last novel, The Peripheral, a time travel techno-thriller in which the author discards the metaphysical baggage that comes with souped-up DeLoreans and killer cyborgs from the future.

The Peripheral (2014), the first book in what Gibson has promised will be a time travel trilogy.

The premise underlying both novels is Gibsonian in the extreme: Assume that physical time travel is impossible. The only way to visit the past is digitally, through information exchange (because information is time-agnostic). Once you make digital contact with the past (via a myserious computer server), voila!—an alternate timeline, or continuum, is created. The alternate history, called a “stub,” is independent of your present continuum, because in your past there was no digital contact from the future. “And that,” Gibson explained in a wide-ranging interview with The Guardian, “spares me all of that tedious paradoxical stuff that bogs down time travel stories.”

It also opens up an almost infinite set of possibilities. The Peripheral, functionally a murder mystery in time traveler’s clothes, jumps back and forth between post-apocalyptic London in the early 22nd century (the master timeline, home of the aforementioned server/digital time machine) and an alternate version of the United States, set in the 2030s. In future London, Wilf Netherton gets pulled into a murder investigation involving a witness who lives in the stub. (It’s as mind-bending as it sounds, only more so, and twice as cool.) Netherton is recruited by the formidable Detective Inspector Ainsley Lowbeer, who solves the London murder and empowers the inhabitants of the stub to begin writing their own future—one in which the stub might, with luck, avoid the worst of the apocalypse that nearly depopulated the Earth in Netherton’s and Lowbeer’s timeline.

That apocalypse? A convergence event called “the Jackpot.” Imagine the most extreme scenarios predicted by climate scientists today, add them together, and crank the dial to eleven. Ecological collapse, mass extinction, famine, civil unrest … and global contagion. Multiple pandemics, ravaging a species dependent on a complex network of systems, natural and manmade, that are revealed by the crisis to be more fragile than anyone thought possible.

The Jackpot casts a long shadow in Agency, too. Lowbeer informs Netherton of a new stub that she needs his help with. This stub represents the future’s earliest known contact with the past—a timeline in which Lowbeer might be able to avert the Jackpot entirely … if she can find a way to defuse its immediate existential threat of impending nuclear Armageddon.

Meanwhile, we’re introduced to Verity Jane, who lives in a version of San Francisco that looks and feels more familiar than anything we saw in The Peripheral. It could be a snapshot from our own timeline—wildfires burning out of control in Napa and Sonoma, tech-bro start-ups chasing the holy grail of artificial intelligence. Verity has just landed a gig for one of those start-ups, beta-testing the company’s new AI digital assistant. Nothing too complicated, she’s been told, just putting the AI through its paces.

The AI interface is an earpiece, a smartphone, and a pair of “gray minimalist” eyeglasses—think Google Glass, if Glass had been designed by Matsuda. The kit is primitive compared to what we’ve seen in Netherton’s world, and even Verity finds it disappointingly generic—until she powers it up and meets Eunice, an AI that passes the Turing test so convincingly, Verity at first believes she is being pranked for a reality TV show. Eunice can’t be AI; she must be a person back at the start-up’s headquarters, playing along until the big “Gotcha!” moment.

Nope. Eunice is everything she seems to be, and more. So real that even the start-up is surprised.

Eunice is also Lowbeer’s indirect gateway into Verity’s stub, soon revealed to be an alternate 2017 in which Hillary Clinton won the U.S. presidential election and the Brexit referendum failed. (Don’t get excited; neither of these events changed the underlying systemic problems that brought us the reality we’re currently experiencing. Things in alternate 2017 are just as dire, only in a different way.) Technological asymmetry between future London and Verity’s 2017 prevents direct communication with the stub at first, so Lowbeer and her agents must “nudge” Eunice “toward greater agency,” hoping she will self-assemble into a system advanced enough to make a difference.

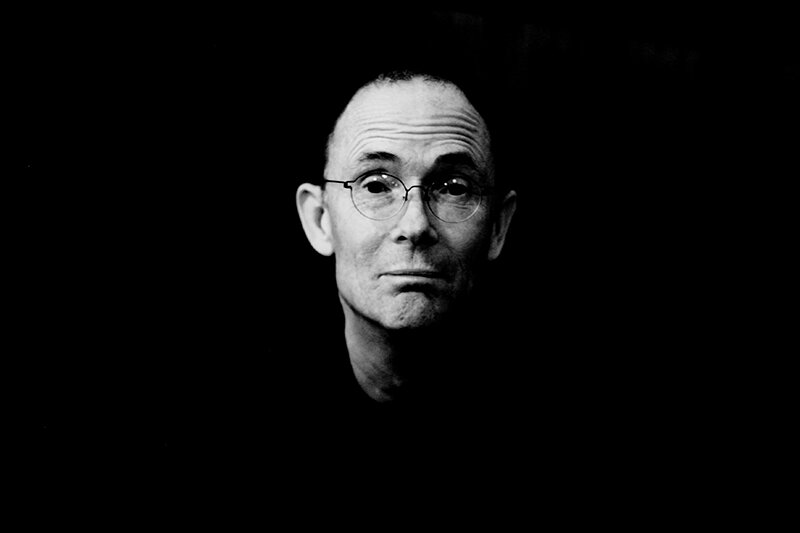

William Gibson. Photo by Frédéric Poirot, 2007.

Gibson launches Agency like a Tesla Model S in Insane mode. Verity barely has time to get acquainted with the most advanced AI in her timeline’s history before she and Eunice are on the run, pursued by ex-military thugs working for the tech-bro start-up, which turns out to have more of a ruthless-stealer-of-decommissioned-secret-military-research vibe than your average Silicon Valley unicorn.

Thus begins an extended chase, in which Verity is passed from node to node in a human network assembled on the fly by Eunice. Beyond her initial decision to trust Eunice and the parade of characters who show up at just the right moments to help her, Verity doesn’t do much for the rest of the novel, except observe what’s going on around her. All the heavy lifting required to protect her (and, by extension, Eunice) from the nefarious company and its goons is done by others. The agency on display in the novel emerges not from any one individual’s actions, but from the way those actions are amplified by social connection and cooperation, all of it choreographed by Eunice, at first with “subconscious” nudges from Lowbeer, and later entirely on her own.

Netherton, observing from the 22nd century, is similarly along for the ride. He is Lowbeer’s intermediary between their timeline and the various stubs they are working in, having a unique talent for explaining the situation in a way that doesn’t make people who learn the truth about living in a stub, like Verity, immediately lose their minds. It’s an ideal arrangement for the newly domesticated Wilf, who can work from his couch and help his wife care for their young son, all while passing critical information back and forth between Lowbeer’s team and Verity and her protectors. (Imagine the job posting: Director of Digital Time Travel Informatics. Once-in-a-lifetime opportunity! Help save alternate timelines from the Jackpot! Strong communication skills required. Must be able to explain complex metaphysics of branching continua to subjects from past eras without inducing mental breakdown. Flexible hours. Work from home.)

All of this is a far cry from the hyperkinetic action one might expect of a sci-fi techno-thriller with a badass time travel premise. In an alternate timeline—or even a vintage Gibson novel—Verity and Netherton would be kicking butt like Trinity and Neo in The Matrix, to our visceral delight.

Instead, Agency’s payoff comes from identifying with Verity and Netherton as they find themselves at the mercy of events utterly beyond their control. No action they could take as isolated individuals, no matter how skilled, no matter how dramatic, will make a difference to the outcome. The only way to survive, the only way to have agency that matters at scale, is to give up the illusion that we are separate, self-contained, wholly autonomous beings; to build networks and communities committed to a common goal, a shared vision and purpose; to trust each other and work together for the benefit of everyone, not just ourselves.

Sound familiar?

Whatever happens in the weeks and months ahead, don’t believe the lie that you are responsible only for your own welfare, or that your welfare is your responsibility alone. Don’t believe that your individual choices won’t make a difference. Agency matters most when we choose to help each other.

We’re all in this together. Cooperate or die.

William Gibson. Agency. New York: Berkley, 2020.

Cadwell Turnbull's new novel — the first in a trilogy — imagines the hard, uncertain work of a fantastical justice.