If you grew up in the 80s or 90s, chances are you know the Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark books. Whether they were in your school library or just whispered about by your friends, the gory artwork created by Stephen Gammell and the bone-chilling stories collected and retold by Alvin Schwartz are likely imprinted into your childhood (and adult?) nightmares (or maybe that’s just us?). This Friday the 13th (muhahahaha) we here at Fiction Unbound wanted to mine our nightmares for your entertainment, so we’re discussing our favorite stories from the three volumes of Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark and how they messed with our heads (in the best way). Warning: Even if you’re a grown-up, these books should be read in daylight unless you’re ready to be disturbed by them all over again.

Amanda Baldeneaux:

For someone with an aversion to horror films in adulthood (my imagination gets REALLY good round about midnight), it surprises me how rabidly my childhood self devoured scary stories, folktales, and novels (Christopher Pike, anyone?). After reading the Short & Shivery collection’s "Tailypo," about a monster who comes to the foot of a bed looking for his hacked-off tail, I slept with my feet tucked up to my tummy all through first grade in fear the monster would wander into my room (in the Netherlands - because I was sure he could cross oceans or that the Dutch had their own tail-less beast) in search of its missing extremity. It strikes me as prescient, now, that even at that age I knew to be afraid of fanged figures looming over me in the dark. While the fangs may be allegorical, I credit inherited cultural memory (because yes, I believe in such things) from all the women before me for the inherent knowledge that both strangers and the dark can be menacing for a girl.

Alvin Schwartz’s Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark opens with a legend similar to my scar-inducing "Tailypo," "The Big Toe." Less sinister than severing a woodland creature's tail, in Schwartz’s version, a little boy innocently uncovers a large toe sticking up in the garden. Not exploring further, he wrenches it from the ground (or a corpse) and gives it to his mother to cook, as one does. After dinner and settling into bed for sleep and digesting, a voice stalks the house, calling out for its missing toe. Whether zombie or ghost we can’t be sure, as some versions end with the storyteller pouncing on a listener, and others with a figure in the chimney who returns the favor of having its toe consumed by eating the little boy.

This is the perfect opening for a book set to scar children for life, because what is scarier than the idea of being devoured? Children know they won't stay children forever, that the ever-looming threat of adulthood stands in the shadows, ready to devour playtime and naps. To a child, play is synonymous with the self, and therefore maturity threatens to consume that self. Don't even have a taste of that toe, kids - once adulthood knows you're there, it will come knocking, forks drawn.

As a child, I feared being devoured literally thanks to Tailypo and the grandma-eating Big Bad Wolf. As I got older this fear evolved into a biologically absurd terror at sharks that (I believed) swam in the freshwater lakes where my family would water-ski. In high school, my Asian Studies teacher gave a lecture on the film Jaws and the great white as metaphor for our own terror at things deep (and buried – like a corpse!) in our psyche rising up from the darkness to consume us, transforming us into the monsters we know we’re capable of being, (the fact that the shark was a great white shark devouring victims is a post for another day). At 17, this lecture blew my mind and resparked my interest in horror, the human attraction to it, and what it tells us about who we are.

Another Schwartz story that I remember and that still has me scarred to this day is The Red Spot. A microstory, it details a young girl who wakes up to find a red spot on her face. Unbeknownst to her, her face played crossroads to a spider in the night while she slept. Her mother tells her not to worry about the spot, but the red spot grows and grows, ultimately exploding during a warm bath and releasing a swarm of baby spiders. There’s much to unpack in these short paragraphs.

To start, it's important to note that it's a girl whose face becomes the incubator for hundreds of spiderlings. Women are the world’s incubators, and most girls (cough, me) grow up terrified of the idea of giving birth (the blood, the screaming... thanks, Hollywood). Schwartz’s description of the spiderling eruption isn’t that far off from some retellings of human birth, a life-threatening feat even with modern medicine. Then there’s the mother telling the little girl to ignore the growing red spot on her face. “Ignore it” is historically our culture’s most treasured piece of advice for girls. Sexual assault? Post-partum depression? The gender pay gap? “Ignore it” is the red-blooded American response to each of these issues. Problematically, leaving the “red spots” of abuse and discrimination to fester and rise to a head while distress goes unheeded yields future consequences. Perhaps not a festering explosion of spiders, but depression? Isolation? Self-harm? Red spots won't let themselves be ignored by the sufferer (shout out to Rose McGowan today). At best, ignoring the "red spot" results in a pop of scattering bugs. At worst… well, that’s too scary to think about.

Danyelle C. Overbo:

The stories in Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, More Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, and Scary Stories 3: More Tales to Chill Your Bones don’t just mess with your head, they stick to your bones. I have vivid memories of scanning the shelves of my elementary school library and finding these books. The sketchy, black and white horrors illustrating the covers and each story spiked my young curiosity and gave me goosebumps. They felt forbidden even though they were there on the shelf for anyone to check out. I would sit on the scratchy gray carpet and skim through the books keeping a wary eye out for adults. I never checked them out that I remember, but I know I’ve read every story. Afterall, what would Mrs. Diblase have said if she caught me looking at these books?

I was not a fan of horror. Not in any sense of the word. Don’t even ask how old I was when I was finally able to take a shower at night without my mother folding laundry in the hallway outside the bathroom. I was a true scaredy-cat. Everything dark, spooky, and isolating would set off tears. So why would I read these books? Perhaps it was the sense of the forbidden. Maybe I was terribly curious because I avoided scary things so much. No matter the reasons, the end result was the same. I was plagued by the monsters that lived in these tales. They never left me. By far, the worst story out of the collection for me, the one that shook me to my core, was "Harold." I hesitate even now to reread it for this post. But there’s that curiosity again…

Thomas and Alfred are cow herders who spend a couple months a year in the mountains with the herd. One day, they decide to make a man-sized doll out of sacks of straw to keep birds out of the garden. They name him Harold after an old farmer they don’t like. They talk to Harold, tell him jokes, and, when they are in a bad mood, they treat him poorly. They hit the doll and smear food on its face. One day, the doll begins to grunt at them. The men are scared, but talk themselves out of making anything out of it. Then Harold begins to walk around. He climbs up on the roof and trots like a horse. The men are afraid and decide to leave the next day. They realize too late that they forgot their expensive milking stools and draw straws to see who has to go back for them. Thomas goes off alone. Soon after, Alfred sees Harold on the roof again, in the distance, he is laying out a bloody skin to dry in the sun.

Part of the horror is in the bluntness of delivery in these tales. My summary was shorter than the story in the book (you should still read it!), but not by much. The thought of a living doll skinning a man alive struck terror in my young heart and still does to this day. I have always treated my dolls with respect, but after reading that, you can bet that I was especially careful to treat them nice!

Not every story has such a gruesome ending. My favorite stories in the collection have somewhat happier endings, like "Room for One More." After reading it, I was kept up at night pondering all the implications of dream warnings and what I would do if I ever got one myself. Would I be smart enough, like the man in the story, to heed the warning? In this tale, a man on a business trip can’t sleep and hears a car outside his window. When he looks out, he sees it is a hearse filled with people. The driver of the hearse says, “There is room for one more” and then he drives away. The following day, the man is waiting for an elevator when one opens that is filled with people. The driver of the hearse is in the elevator and says, “There is room for one more.” The man declines. The elevator then crashes, killing everyone on board.

I also loved "High Beams." Many versions of this story circulate as urban legends as well. In this story, a woman driving her car is chased down a highway by a truck who keeps turning on its high beams. We’ve all heard this one, right? It turns out, as she pulls into her driveway calling for help, that the truck following her was saving her life because a man was actually in her back seat about to attack her. These crazy stories! I’m happy that I can read them as an adult and appreciate their quirky humor like I never could when I was little. Now, if you’ll excuse me, it’s getting dark out. I’m definitely not going to run around my house turning on every light...

Sean Cassity:

Stephen Gammell

Reading Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark felt natural to me as a ten-year-old. After all, my older sisters had been telling me versions of some of these stories since before the book came out. The simple language Alvin Schwartz used in sharing his collection of folklore wasn’t so different from the vocabulary of my preteen sisters. I wouldn’t be surprised if I read the entire book in their voices.

What really stamped the book in my imagination, what it added that even my sisters’ half whispered voices in our dim living room, lit only by the logs in our cast iron fireplace, could not supply, was the pictures. What I saw in my sisters’ tales was a television screen, the characters as crisply outlined as the actors in daytime rerun of Bewitched. Stephen Gammell’s artwork dashed that to pieces.

Forget borders. Forget the edges of things. The world of Stephen Gammell’s pencils and brushes is frayed, dissolving, and, especially, dripping. He captures the quality of trying to make out shapes in the darkness; the pareidolia of the not quite seen. Before it resolved, before it manifested into the horror on the page, it may have seemed, there may have been time to hope, that the ghoul before you was just a coat over a chair, a bent tree in the mist. These pictures grasped at stories that in their telling were often quite quaint and pulled them down into the dreadful.

The illustrations are at least as important to the book’s impact as the text. I can’t believe we would still be talking about Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark today if it had premiered with safer, more conventional children’s book artwork. Of course, without these horrifying images and their dependence on a Gothic mixture of both the craggy and the blurry, the book might not have found itself on banned book lists for so much of its life. The book’s publisher, Harper Collins, seems to have recognized Gammell’s art for its share in the controversy and attempted to rerelease the series in 2011 with more timid, cartoony illustrations from Brett Helquist, illustrator for the Series of Unfortunate Events books. Backlash from readers was strong and Stephen Gammell’s original art was restored in the paperback box set released last July.

Stephen Gammell’s children’s book credits date back to 1973, eight years before the first publication of Scary Stories. A self-taught artist, his unique perspective, where nothing is quite solid, is evident even in these cheerful early books. He worked on a couple of supernatural titles in the years leading up to Scary Stories and you can see his shadow world emerging before it explodes full force in the first Scary Stories volume in 1981. With over 50 titles to his credit as a children’s book illustrator he continues to produce great art for a large breadth of genre’s. While it’s easy to acknowledge the fantastic variety in his work, he will always be remembered for the ghastly apparitions he shared with us in three thin volumes that are always checked out of the library.

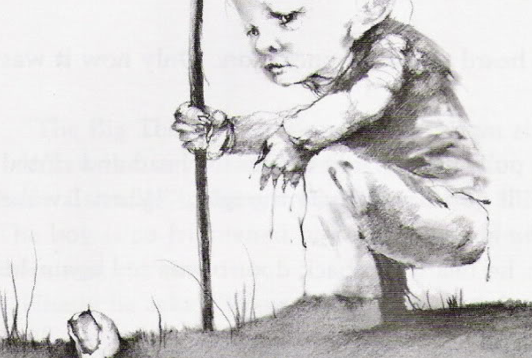

Those of us who found Scary Stories as children all have a Gammell image that sticks most with us. Scarecrow "Harold" and the spider-erupted face of "The Red Spot," both from the third volume, are popular examples. For me it’s the very first image where the stories get started in the first book, the crouching little boy who has just discovered the "Big Toe." The large, fist-sized toe is supposed to be the horrific catalyst here. So why is the boy so creepy? His oversized ear sits far back on an already oversized head and his fingers and back pocket are dripping. His hoe is dripping. If these are the normal people in Stephen Gammell’s vision, god save you from the walking dead.

For more scary story recommendations this Friday the 13th, check out our Halloween Thrills post from last year and keep an eye out for our retro Halloween recommendations post coming later this month! What about your favorite Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark? Please share in the comments below.

There is so much out there to read, and until you get your turn in a time loop, you don’t have time to read it all to find the highlights.