The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, Edgar Allan Poe’s only novel, is a racist mess. After a mutiny at sea, shipwreck and some lifeboat cannibalism, the titular Pym and the crew of the Jane Guy find themselves on Tsalal, an island of inhabits so black, even their teeth are black—even the island’s water is a purpled black. By Poe's account, the Tsalalians are savage, subhuman gargoyles, and of course they betray and try to kill the white Pym, of course he outwits them and escapes. As he drifts south to Antarctica, the Tsalalian he’s taken along as a hostage and guide, Nu-Nu (0__0), becomes increasingly terrified of the white, snowing skies, the white birds screaming Tekeli-li!, and the white continent approaching. As Nu-Nu expires in fear, Poe ends the novel with one of the most bizarre, haunting images in American literature:

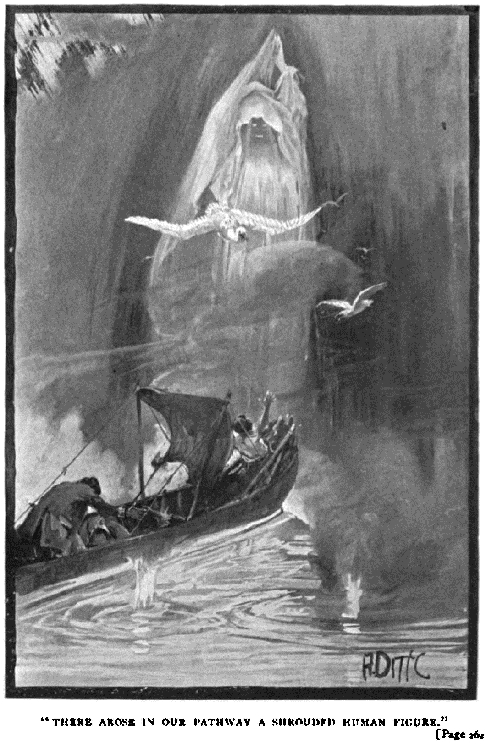

And now we rushed into the embraces of the cataract, where a chasm threw itself open to receive us. But there arose in our pathway a shrouded human figure, very far larger in its proportions than any dweller among men. And the hue of the skin of the figure was of the perfect whiteness of the snow.

The End. There’s a confused, unsatisfying post-script, but Pym’s narrative ends exactly there, in what Toni Morrison calls one of the “figurations of impenetrable whiteness” that follow African or Africanist figures in (white) American literature with remarkable frequency. Think of the snow at the summit of Hemingway’s “Kilimanjaro,” the white wasteland at the end of Faulkner’s Absalom! Absalom!, the baffling, white marble at the end of Styron’s Confessions of Nat Turner, the arctic silence that concludes Bellow’s Henderson the Rain King. These images “clamor,” writes Morrison, “for an attention that would yield the meaning that lies in their positioning, their repetition, and their strong suggestion of paralysis and incoherence; of impasse and non sequitur.”

In her brilliant monograph Playing in the Dark, from which the above is taken, Toni Morrison traces how early American literature used an available, enslaved black population as figures of negative identification, a shadow that could show an anxious, isolated new nation what it was by contrast. The presence of black characters observed by white protagonists in America’s early fiction—like Jim in Huckleberry Finn, or Nu-Nu in Poe’s Pym—“is the vehicle by which the American self knows itself as not enslaved, but free; not repulsive, but desirable; not helpless, but licensed and powerful; not history-less, but historical; not damned, but innocent; not a blind accident of evolution, but a progressive fulfillment of destiny.”

Mat Johnson’s Pym (2011) exists in conversation as much with Morrison’s Playing in the Dark as with Poe’s original Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym. Our hero, Chris Jaynes, a recently canned professor of African-American Literature, levels a blistering critique of Poe’s fever dream of a novel:

You want to understand Whiteness, as a pathology and a mindset, you have to look to the source of its assumptions. … That’s why Poe’s work mattered. It offered passage on a vessel bound for the primal American subconscious, the foundation on which all our visible systems and structures were built.

Jaynes discovers a slave narrative that proves Poe’s Pym was cribbed from a true story, and sets off to Antarctica in hopes of finding Tsalal. To Jaynes, Tsalal is a paradise untouched by a history of European exploitation and slavery, and free from the toxic mythology of white supremacy. What he discovers, however, is the truth of the shrouded white giant that haunts The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym’s final sentence.

Johnson’s Pym is marketed as a comedy, or at least satire, but—and I mean this in the best of ways—it’s about as funny as dysentery. While the voice is always witty, its driving emotion is a thrilling, unapologetic anger; maybe the best sentence in the book is a footnote on Poe’s publisher, the Southern Literary Messenger, and its “pro-slavery” stance: “That is to say, it advocated lifelong human bondage for those of African descent, as well as their children and grandchildren, great-grandchildren, et cetera, for eternity.” There’s also a marvelous running critique of (a thinly disguised) Thomas Kinkade and his cloying paintings as an allegory for the white “post-racial” vision, a false, unnatural, and sickly-bright color scheme that simply paints over the ugliness of modern and historical injustice.

Once Jaynes and his all-black crew arrive in Antarctica and make contact with the “snow honkies,” things get very grim indeed. I’m trying to avoid spoilers, but I’ll say that the apparent destruction of global civilization is the least of Jaynes’ worries. I’ll say also that Pym’s structure is a satisfying photo negative of Poe’s original, with, for example, an isolated island of horrific white savages threatening the intrepid black protagonist.

But Pym is a book of nightmares, a book about how slavery haunts the American black imagination. To have Laura Miller and Jonathan Lethem proclaim how “hilarious!” it is on the book jacket brought to my mind the nervous laughter of a white cocktail party listening to the one black guest tell a joke about Nat Turner.

How does slavery continue to haunt the American white imagination? If Pym’s question is How could this have been done to us?, are creators asking the white corollary: How could we have done this? The white nightmare of slavery is social continuity—the unnerving knowing that the people who tolerated and perpetuated slavery are not fundamentally different from us today. We share the same DNA; although we’ve amended the Constitution to good effect, the Bible and the Declaration of Independence are just as they were when this country thought them consistent with the enslavement of millions.

The novel of the slaver is rare, if one exists at all; the Oscar-winning film from the perspective of a slave-owning family is hopefully behind us. To the extent slave-holders are depicted today, they are villains in stories told from black points of view. This is probably a good thing.

But speculative fiction allows us to process such anxieties at a psychic remove—“the opportunity to conquer fear imaginatively and to quiet deep insecurities,” as Morrison describes the comparable genre of the American gothic romance. So, we have the very populous sub-genre around artificial intelligence, in which the protagonists, us, exert complete authority over a certain kind of sentient life. The word ‘robot,’ after all, comes from the Czech word for ‘forced labor.’ Sometimes the machines rise up and kill us, as in the slave rebellions of Battlestar Galactica and Terminator; but mostly we retain control over our artificial servants, a far more disturbing dream, because we never get the cathartic punishment the crime deserves.

Robert Picardo as The Doctor.

The Emergency Medical Hologram on Star Trek: Voyager (“The Doctor,” for short) was the culmination of a line of self-aware holodeck characters, their bodies just projected light and force fields and their minds only computer programs. While Star Trek: The Next Generation always maintained the android Data was a living being, deserving of civil rights, the writers were far more ambivalent about these semi-alive figures whom the crew could create, control, have sex with, and destroy without any notion of consent. In ‘Latent Image,’ the Voyager crew reprogram the Doctor because they view his crisis of grief, guilt, and self-doubt as a malfunction, a feedback loop between his ethical and personality subroutines. Captain Janeway compares the Doctor to a replicator—a machine to serve drinks, basically—to explain why he doesn’t deserve the right to consent to his own lobotomy. (Ultimately, they work it out, and the Doctor is allowed to process his crisis through psychoanalytic therapy. I mean, this is still Star Trek.)

The Doctor is also a comic character, his irritable and irritating bedside manner played for laughs. So is C-3PO: a fussy, neurotic artificial figure of fun who calls the protagonist ‘Master Luke.’ So is Frozen’s Olaf the Snowman, an artificial, sentient, and uncontroversially obedient being created by the heroine Elsa—and who survives only at her pleasure. Their antics annoy and exasperate our heroes, which socializes us to the unlimited control the humans have over these artificial bodies; on more than one occasion, C-3PO and the Doctor are switched off for pestering their masters. That's... weird, isn't it? Kind of scary? Not to be a buzzkill—please be assured, I still love Star Trek and Star Wars as much as when I was a kid—but similar comedic strategies, like the minstrel show and racial kitsch, were deployed to support slavery and Jim Crow. If the servant is too foolish, or too annoying, to use his freedom well, does he really need it at all?

Hilarious!

The point of view in ‘Latent Image’ is strange; at first, we’re positioned alongside the Doctor, and certainly we sympathize with him, but subtly, the narrative shifts to privilege Janeway and her ability to choose what to do—this is not really a story of the Doctor’s powerlessness, but of Janeway’s hideous power. Even her kind gestures at the end, as she keeps vigil, reading, while the Doctor stews on a holographic couch, carry the menace of a master’s wearied patience.

I haven’t even mentioned the Borg yet; that will have to be another essay, but it is remarkable how often the Borg, a race of cyborgs who literally enslave civilizations, are positioned to comment on and critique the ostensibly benevolent humans. I will point out this: the very first episode to feature the Borg begins with Chief Engineer Geordi LaForge, a black man whose best friend is the sentient machine Data, joking to an ensign she doesn’t have to be polite to the replicator, because it’s only a machine. It’s only there to serve her drinks.

Like speculative fiction, comedy is a space of the irrepressible imagination, the impolite anxiety that taboo that can't quite contain. It would be unthinkably strange if the two hundred years of American slavery that so profoundly shaped our political and economic institutions had quietly slipped out of the national imagination; but such a large, dangerous thought is hard to contain in small type. Speculative fiction allows us to see it at a safe distance, and comedy allows us to close our fingers in a circle around it, pretend we've trapped it. The idea of re-enslavement is too bottomless, too terrifying; the story of capture by Antarctic giants is easier on the gut; the bleak comedy of bondage to snow honkies is something you can take on a plane. So perhaps, Pym is best accepted as a speculative satire, and the Doctor, a comic character in a TV space opera, in which readers of different backgrounds can still process what humanity is capable of enduring—and doing.

In the crucible of catastrophe, we learn deeper truths about love, loyalty, and compassion.