“Soon her eye fell on a little glass box that was lying under the table: she opened it, and found in it a very small cake, on which the words ‘EAT ME’ were beautifully marked in currents.”

Margaret Atwood’s The Edible Woman, published in 1969, added loud resonance to the written resistance against prescribed women’s and men’s roles, ridiculing the culturally upheld notions that women were baby-making homemakers who needed a man’s hand to guide their feeble thoughts, and that men were brawny sacks of muscle who earned money and shot things. Atwood’s The Penelopiad, published in 2005, retells the Odyssey narrative through the eyes of Odysseus’s steadfast wife, Penelope, and her 12 maids. Despite being set in ancient Greece, gender expectations remain (originated?) the same: Penelope is expected to play the part of virginal mother, and Odysseus the wily, swashbuckling manly-man.

Consumer Culture

In both books, narrators Penelope and Marian guide the reader through a Wonderland of cultural patriarchy in ancient Greece and Vietnam-era Canada, where one’s body and soul is a featured item on life’s menu. Penelope, the daughter of a king, is a prize to be won in a tournament, bearing the title of “wife” rather than “trophy” at the event’s conclusion. The larger the dowry and greater the beauty of the bride-to-be-won, the more feverishly the men struggle to out-wrestle, run, and archery each other. Woe to the sensitive man who would rather write poems or study insects when it came to wife-winning; bachelorhood or a lowly scullery maid awaited him. Penelope is well-aware of her status in these contests, as none of the men were allowed to see or speak to her before the competition began:

“I know it isn’t me they’re after, not Penelope the Duck. It’s only what comes with me – the royal connection, the pile of glittering junk. No man will ever kill himself for love of me.”

“Who am I, then? Tell me that first, and then, if I like being that person, I’ll come up: if not, I’ll stay down here till I’m somebody else.” – Alice in Wonderland. Illustration by Jessie Willcox Smith

The Edible Woman’s Marian, a twenty-something, college-educated working girl navigating the dangerous waters of ‘not-married-yet-dom,’ edits surveys for a market research firm, in an office where new flavors of canned rice pudding are a source of excitement. As a sense of dissatisfaction with the status quo begins to rise, Marion comes to see herself as a commodity no different than rice pudding. When invited to dinner by male friends, she finds herself on the receiving end of soliloquies and philosophical lectures, all the while asked nothing except her thoughts on the elegance of the dinner plates:

“She was considering the total absence all evening of any reference to or question about herself, though she had assumed she was invited because the two room-mates wanted to know more about her. Now, however, she thought it more likely that they were merely desperate for new audiences.”

Despite having plenty to add to the conversation, Marion steers the course preferred by Penelope when interacting with Odysseus:

“It’s always an imprudence to step between a man and the reflection of his own cleverness.”

The Rabbit Hole

As Marian tries to hide the food on her plate in her purse, her dinner companions explain the “sexual-identity-crisis” in Alice in Wonderland to her:

“If you only look at it closely, this is the little girl descending into the very suggestive rabbit-borrow, becoming, as it were pre-natal, trying to find her role as a Woman.”

As the graduate student, Fish, continues his speech, Atwood cleverly aligns each of the stunted Alice characters with the population of her own story. Marian’s friend Clara “rejects Maternity when the baby she’s been nursing turns into a pig.” Her roommate, Ainsley, is the Queen with “her castration cries of ‘Off with his head!’” Duncan, a misanthropic graduate student, is the Mock-Turtle, “enclosed in his shell and his self-pity, a definitely pre-adolescent character.” Peter, Marian’s boyfriend turned fiancé, is the “dictatorial Caterpillar,” telling Marian what to order in restaurants, how to better style her hair, and what he expects of her as his wife.

While the most overt critique in each book focuses on the treatment of women, both the male and female characters suffer from their prescribed gender roles. In both books, each character is stunted by fears of growing up. Where the men have Peter Pan syndrome and are coerced into a machismo characterized by brawling, warring, fishing, and drinking Moose Beer (anything less would make one a “fairy”), the women are silenced and cloistered into the image of idealized, virginal motherhood (where anything less would be to have “loose morals”).

1960’s Peter gets to be both child and ideal man by crying over his last single friend’s engagement while posing his lip-sticked girlfriend in front of his gun collection. Odysseus gets to play both roles by stalling his return from war, where he fought like a hero, to his wife and child. His adventures may be well recollected through a mythical lens, but Penelope has a more pragmatic interpretation of what he was doing all those years at sea:

“Odysseus had been in a fight with a giant-eyed Cyclops, said some; no, it was only a one-eyed tavern keeper, said another, and the fight was over non-payment of the bill…Odysseus was the guest of a goddess on an enchanted isle, said some…it was just an expensive whorehouse, and he was sponging off the Madam.”

Penelope gains her insight into the dangerous expectations placed on women and men through both her long waiting period, and in the afterlife. Marian begins to gain perspective as she comes to see her food as a consumable commodity no different than herself:

“She became aware of the carrot. It’s a root, she thought, it grows in the ground and sends up leaves. Then they come along and dig it up, maybe it even makes a sound, a scream too low for us to hear, but it doesn’t die right away, it keeps on living, right now it’s still alive…”

Creepy Carrots, by Aaron Reynolds and Peter Brown

Blame it on the Sluts

Penelope shares narration with her 12 maids, who punctuate her story with a sometimes embittered, sometimes sorrowful retelling of their own story: their murder at the hands of Odysseus and Telemachus. Enlisted as spies by Penelope to keep tabs on the unruly suiters, the maids use their bodies to keep the hall of unwelcome men occupied. For sexual promiscuity that disgraces the master of the house, Odysseus has them hung from a ship’s mast. In Marian’s world, sexual purity was equally valued. Her friend, Len, only has an eye for young, virginal girls:

“The supposedly pure, the unobtainable, was attractive to the idealist in him; but as soon as it had been obtained, the cynic viewed it as spoiled and threw it away.”

Despite his desire for the sexually pure, his Peter Pan syndrome makes the idea of marriage and children as abhorrent as a “spoiled” woman:

“‘But you’ve got to watch these women when they start pursuing you. They’re always after you to marry them. You’ve got to hit and run. Get them before they get you and then get out.’ He smiled, showing his brilliantly-polished white teeth.”

Len is a predator just as Penelope’s suitors were, wanting the woman as prize rather than the woman herself. When the tables are turned on him by Marian’s roommate, Ainsley, he is none too pleased to learn he has been fooled into sleeping with and impregnating a woman closer to 30 than 20:

“All along you’ve only been using me. What a moron I was to think you were sweet and innocent, when it turns out you were actually college-educated the whole time!”

This revelation into her friend’s true nature leaves Marian further unsettled, both with her own sense of self and her friendship with a man of Len’s caliber:

“Len had displayed something hidden, something she had never seen in him before. He had behaved like a white grub suddenly unearthed from its burrow and exposed to the light of day. A repulsive, blinded writhing.”

Len is another candidate for the book’s adolescent Mock Turtle, with his prime education in Lewis Caroll’s fictional curriculum:

“Reeling and Writhing of course, to begin with,’ the Mock Turtle replied, ‘and the different branches of arithmetic-ambition, distraction, uglification, and derision.”

The Mock Turtle, illustrated by John Tenniel

To escape pending fatherhood, Len quits his life and takes refuge in Clara’s nursery, finally fulfilling his true desire to remain an adolescent forever. Len’s downfall helps Marian see the trap she’s walked into more clearly: that rather than partner, she’ll be a mute side-dish to Peter’s life. She shares this insight with him by baking a cake in the shape of a woman and feeding it to Peter, an edible effigy in place of herself.

Unfortunately for Penelope, she didn’t have the safety-net of college and work to insulate her from her fate as edible goods:

“And so I was handed over to Odysseus, like a package of meat. A package of meat in a wrapping of gold, mind you. A sort of gilded blood pudding.”

Atwood is well-aware of her indulgence in symbols, and gives the hanged maids the last word:

“You don’t have to think of us as real girls, real flesh and blood, real pain, real injustice. That might be too upsetting. Just discard the sordid part. Consider us pure symbol. We’re no more real than money.”

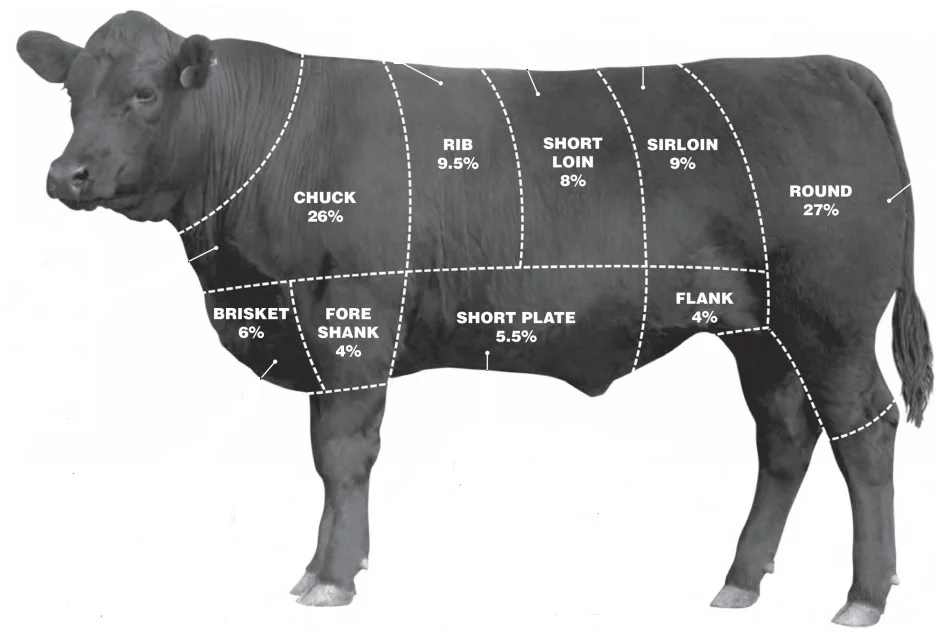

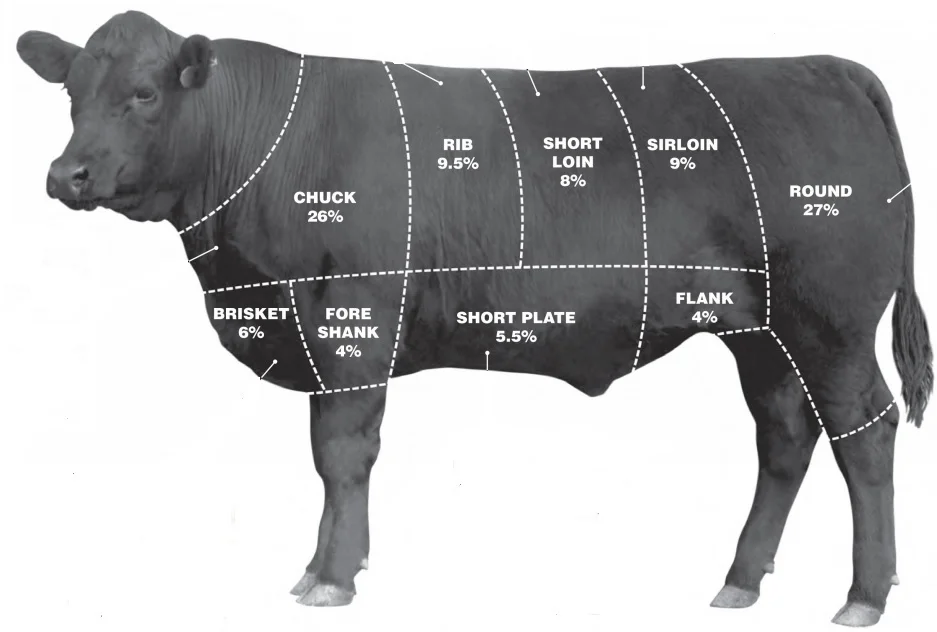

Angus beef chart, American Angus Association

Fiction Unbounders come together for a pile-on review of Margaret Atwood's latest, The Heart Goes Last